From its first incarnation in a former warehouse in Gloucester Docks (where I hope the City Council is still rueing not having made it possible for him to stay), the Museum of Brands has established a consistent approach to its displays. The major part is a decade-by-decade timeline, with cases full of the everyday items one would have found in a household of the time starting with the Victorian era when brand identity first started to become a recognisable part of the domestic scene. Within those chronological arrangements, there are themed cabinets taking a dive into food, toys, or special occasions such as coronations and jubilees. The 1940s section, of course, has a major focus on the war, but stays true to the principle of showing what would have been found in the home, rather than being diverted into militaria. That said, there are some lovely children’s books and games trying to make light of the hardship and danger faced by kids in Britain’s blitzed cities.

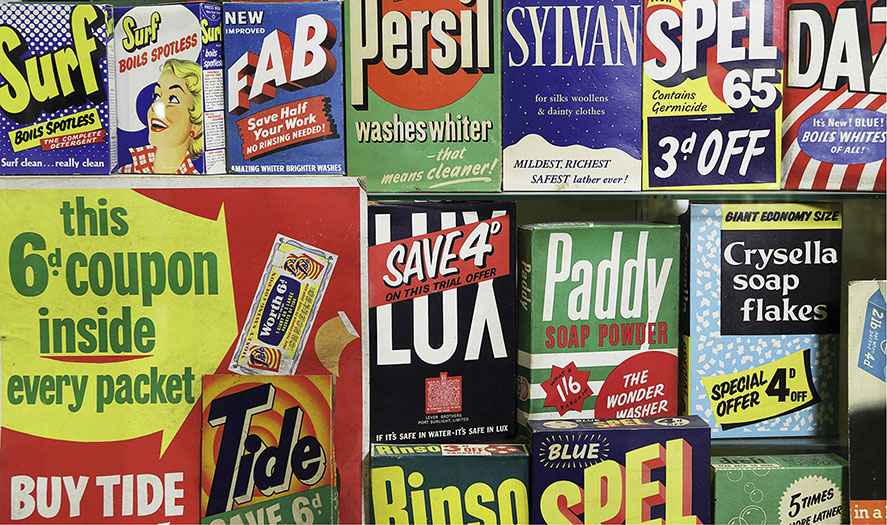

Needless to say, it’s the post-war sections where Mrs M. and I start to get excited. The 1950s displays are packed with the sort of stuff we’ve been collecting over the years, sparking a constant flow of “got one of those” or “cor, wouldn’t I give for one of them”. As the corridor bends into the 1960s and 70s, though, the nostalgia really kicks in as we’re confronted by the things we grew up with – the toys we played with, the tins and packets our mums cooked from, the sweets we craved.

Forgotten products spring back to life (bringing with them tastes and smells buried deep in the subconscious), along with the memories of the things you always wanted but weren’t allowed to have. It’s fascinating listening to the reactions of other visitors, too – even if you couldn’t see the individuals, you could date them to within a few years by their reactions to the items on display. Nor is the Museum trapped in a perceived golden age of the baby boomer era and before; there are new cabinets springing up regularly reflecting packaging styles and imagery of recent years – everything from the Spice Girls to One Direction (our footsteps quicken at this point).

By this time, you’ll probably be in need of a coffee and a slice of cake in the rather nice café (well, who couldn’t love a backdrop of dozens of vintage radios) before launching into the second part of the Museum’s displays which concentrate on particular design themes. There are some wonderful collections demonstrating how well-known brands have evolved to embrace new packaging technology whilst maintaining a common brand image – step forward Bovril and Colman’s Mustard to name but two, plus others to show how the packaging itself has evolved, providing yet another reminder of how fundamental everyday design is to the way we live, and a sobering reminder of what we take for granted in a consumerist society. Playing in the background are some of the great – and not so great – TV ads, echoing the static displays by illustrating how brands are put across in the brief minutes of a commercial, starting with the very first Gibbs Toothpaste ad. to air on UK television. There are temporary exhibits as well, making it worthwhile to pay repeat visits (and you’ll never take it in all at once anyway) – punk rock and advertising jigsaws were two of the examples when we were there.